Following the failure of several prominent banks in the U.S. and the forced rescue of Credit Suisse in the first quarter, financial sectors remained largely resilient in 2023. This upheaval, triggered by concerns around banks’ unrealized losses, was more pronounced than anticipated in the U.S., prompting sizeable support measures from the Federal Reserve to contain risks and restore depositor confidence in small-to-medium sized banks there. These negative effects were largely contained to the U.S.

The tight monetary policy environment yielded a tightening of some financial conditions as anticipated, but the accompanying slowdown in lending and rise in non-performing loans (‘NPLS’) was relatively mild in most countries. Recent trends point to more effective tightening of banking conditions in 2024 as the lagged impact of higher interest rates, the quickly waning benefits of COVID-19 pandemic-related support measures, and slowing economic growth weigh on debt servicing capacity. The same factors that supported stability in 2023 remain in force for 2024, although some tail risks exist to our relatively modest outlook for asset quality deterioration in 2024.

1. Nominal credit growth rates will remain resilient, although ghost deleveraging will continue in most countries, acting as a drag on growth.

Lending will continue to grow in nominal terms in most regions driven by still-high levels of inflation, although in a more contained fashion than in 2022 and 2023. We are forecasting that two-thirds of our covered economies will record lower credit growth in 2024 compared with 2023 estimations owing to higher interest rates and slowing economic activity. This will extend “ghost deleveraging” in emerging markets — a trend observed over the past decade where credit expands in nominal terms, but below its long-term trend as measured by the credit-to-GDP gap. This cautious stance from banks will weigh on economic growth, constraining both corporate investment and household spending. Such credit tightening already has affected a significant proportion of countries in all regions, although it has been more prevalent in economies in Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa. We expect this trend to continue in 2024.

2. Credit risks will remain elevated, resulting in a continued rise of NPL ratios.

Slowing worldwide economic growth and prolonged higher interest rates will weigh on borrowers’ loan repayment capacity, leading to higher impairment in 2024, shown by rising NPL ratios. We forecast the majority of economies under our coverage to register higher NPL ratios in 2024 than in 2023. This increase is expected to remain relatively mild. For households, a key asset quality risk is that existing fixed rate mortgage loans will need to be refinanced at far higher rates in many countries. This is predominantly likely to occur in Europe. Real estate sector risk is also a concern in Asia, particularly in China and Vietnam, where large bank exposure to the sector and falling real estate prices will put pressure on banks’ asset quality. For corporates, higher funding costs on both bank loans and capital markets financing will place increased pressure on their repayment capacity, which is likely to trigger a higher level of bankruptcies. For the US and other developed economies, the falling prices of commercial real estate, lower rental income, and higher interest rates remain a key tail risk to asset quality.

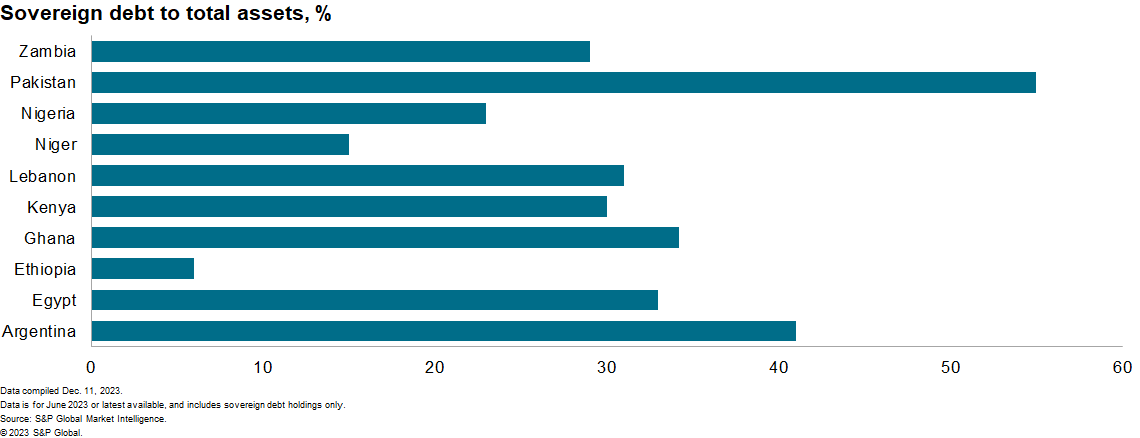

3. Sovereign debt concerns will remain elevated in debt-stressed economies as domestic banks remain the primary source of funding for emerging and frontier markets largely locked out of international capital markets.

Given higher stocks of public debt following the COVID-19 pandemic and limited access to international capital, banks in emerging markets will face increased pressure to lend to their domestic governments, increasing bank-sovereign linkages. This increases banking sector vulnerability to sovereign debt distress and arrears accumulation. This risk remains a strong concern for 2024, because of increased sovereign debt unsustainability in several emerging market countries. Between 2020 and 2023, Zambia, Chad, Lebanon, Ghana, and Sri Lanka defaulted on their external debt. In January 2023, Ghana notably concluded a domestic debt restructuring (DDEP) that significantly impacted banks’ profitability and capital ratios given banks’ large holdings of sovereign debt.

4. Foreign currency shortages will remain pronounced in some jurisdictions.

Foreign currency (‘FX’) shortages are likely to be more pronounced in 2024 in specific jurisdictions — including Lebanon, Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, and many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (‘SSA’) — reflecting higher debt service costs in emerging and developing countries, weakening local exchange rates against major trading currencies, and inadequate foreign reserves. Higher interest rates and capital flight from emerging economies will also negatively impact the cost and availability of foreign-currency funding for banks. This could cause difficulties for banks to roll over foreign-currency debt and create foreign exchange asset and liability mismatches that would have adverse impacts on banks’ capital ratios and profitability. The ongoing foreign currency shortage is likely to force central banks to mandate banks to institute withdrawal limits to preserve their foreign currency holdings to meet FX-denominated obligations as they become due. Risks to the banking sector are greater where foreign currency denominated lending is a larger share of the total and where reliance on foreign funding is largest.

5. Capital preservation is gaining renewed focus for regulators given asset quality concerns.

Capital preservation has been a key area of focus for authorities in recent months and we expect this to continue in 2024. Although capital positions appear robust, regulators are concerned about future asset quality deterioration and are likely to take steps to bolster financial soundness. The US is reportedly considering higher capital requirements for banks in 2024. We expect EU regulators to challenge banks on loan loss provisioning practices following their identification of inconsistent expected credit loss estimation practices in late 2023. Regulators are likely to retain heightened capital-based measures, such as the countercyclical capital buffer, even in the absence of credit booms. Restrictions on dividend payments also are likely to be extended in some jurisdictions. Preventative borrower-based macroprudential measures, such as imposing higher risk weightings for real estate loans, are likely to be considered by regulators seeking to address identified systemic risks and vulnerabilities pre-emptively.

6. Asset price corrections remain a vulnerability, although eventual monetary policy loosening should reduce banks’ unrealized losses.

Following the failure of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023, bond price declines later in the year (October 2023) renewed concerns over expanded pending unrealized losses on banks’ holdings of debt. Unrealized losses on bank balance sheets outside the US did not generate financial stress comparable with that in the US in early 2023. Still, they have had a pro-cyclical effect on monetary policy, curtailing banks’ willingness to extend new credit and encouraging tighter lending standards while resources are tied up in debt securities valued at a loss. As monetary policy pivots towards an easing phase of the economic cycle in 2024, bond price recovery over the coming 12 months should reduce these losses. This should most benefit banks in Latin America, emerging Europe, and other developing economies that raised policy rates earlier and more quickly and have managed to lower inflation faster than in advanced economies. Banks in the eurozone are likely to see unrealized losses persisting at least until the second half of the year given later forecasted monetary policy pivots. Even where policy rates are declining, implementation of plans to reduce central bank balance sheets after their rapid growth during the pandemic will worsen the supply/demand balance in debt markets. Such policy action represents an effective tightening action and is likely to slow or delay bond price recovery and the reversal of unrealized losses.

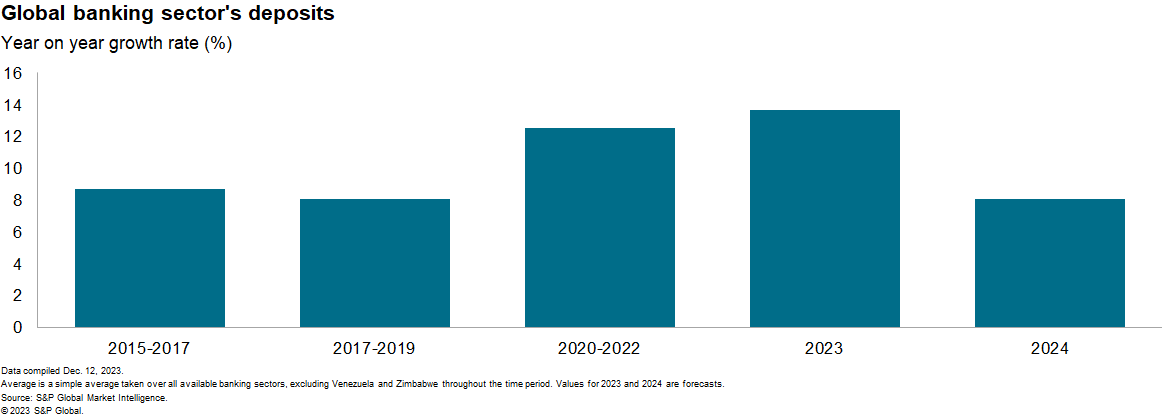

7. Slowing deposit growth will increase bank funding costs, hurting profitability.

Deposit growth is forecast to slow in 2024 in two-thirds of the banking sectors under our coverage. This will increase banks’ funding costs as a combination of tighter financial conditions and weak economic performance will dampen non-financial sector balance sheet growth. The rapid deposit growth rates experienced through the pandemic, as households built up saving buffers, are unlikely to continue. Instead, we project annual global (excluding Venezuela and Zimbabwe) deposit growth to slow to single digits in 2024 versus about 13% between 2020 and 2022. As a result, banks will be forced to offer higher deposit rates to stem deposit withdrawals and to reflect the likelihood of greater competition for deposits from their domestic peers. Where banks seek recourse to wholesale markets, prior monetary policy normalization will require banks to issue debt at historically higher levels and in tighter markets, further squeezing their liquidity and profitability.

8. Merger and acquisition (M&A) activity is likely as larger bank groups seek to expand in core markets and smaller banks exit given the challenging environment.

M&A activity has largely stalled in many emerging markets since the start of the pandemic as heightened uncertainty in the global economy reduced the appetite for bank purchases. We anticipate market sentiment will change. Improved recent profitability and financial sector resilience should encourage larger bank groups to resume cross-border expansion, consolidating their market share in core markets. Smaller and weaker banks experiencing higher funding costs reflecting increased competition for deposits, with lagging technological capabilities and in some sectors higher taxes, will be foremost likely to undergo consolidation, notably in emerging Europe and potentially in Sub-Saharan Africa, where many banking sectors have a large number of small banks.

9. Commercial banks will remain under pressure from fast-growing fintech firms.

Excluding Nubank in Brazil and Tinkoff in Russia, fintech banks have achieved most of their growth via deposit mobilization. They have not yet significantly expanded into credit disbursement, as their business models are usually based on holding short-term safe assets rather than lending. Most fintech firms will continue this approach through 2024. We expect fintech growth to continue accelerating, particularly in their role as deposit collectors for retail customers and SMEs and as a payment channel. Over time, as fintech acquires a more relevant role, we do expect them to start conducting traditional lending, although this is unlikely to happen in most economies until at least 2025. For the few countries with more robust development of the fintech sector and where those operations are now closer to those of conventional commercial banks, we expect regulators to tighten supervision. Development of a clear regulatory framework should assist the largest fintech firms to expand their commercial lending activities. Smaller institutions will face higher costs, increasing pressure to consolidate or merge into larger banking groups (or exit the sector).

10. Further advancements with central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) is expected.

Given sizeable ongoing investment into blockchain technology by governments, banks, and other private sector entities, it is likely that significant further advances will be made in 2024, both towards wider use of CBDCs and private sector use of new technologies. As a result, banking sectors are increasingly exposed to being undercut in several traditional product areas (such as foreign exchange, securities settlement, and cross-border payments) by lower-cost state initiatives or sizeable private sector early movers offering cheaper and near-instant cross-border and domestic payment and settlement arrangements. Progress is likely in 2024, notably in markets like mainland China and India, with the latter having announced plans to introduce a CBDC within 2024. In most global banking systems, an expanded government presence via CBDCs is more likely only in 2025 or beyond, given extensive pilot testing and the need for legislative initiatives prior to implementation.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here