This report is jointly produced with John Abbott, Principal Research Analyst — Applied Infrastructure & DevOps for 451 Research a part S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The chip industry sits at the nexus of national security and economic development policies. That has resulted in a race both in supporting national investments in the semiconductor sector as well as escalating restrictions against sharing technology.

The US CHIPS and Science Act is a prime example, designed to fix supply chain weakness, boost national security, and maintain a competitive lead in the face of heavy state support for computing technology in other countries. The act has attracted investment in six major US semiconductor plants, known as fabs, although only a few funding awards have been made in the US so far.

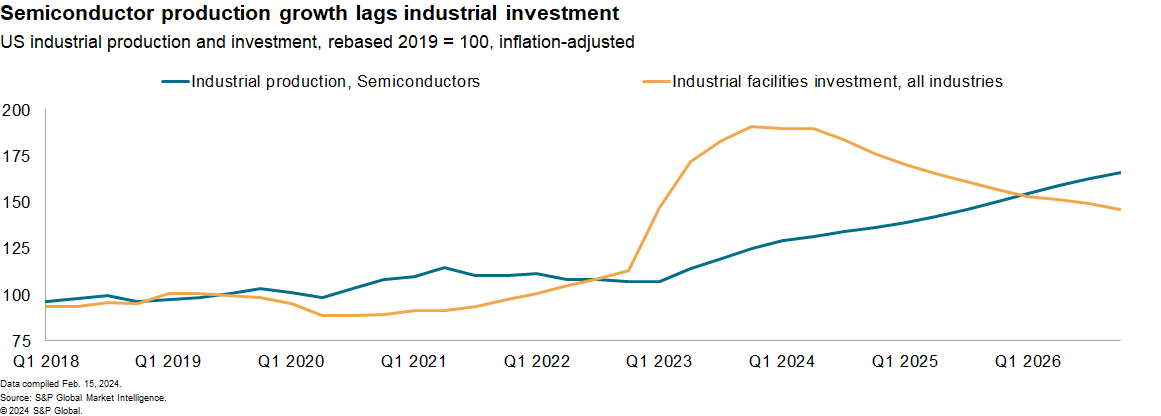

The building of facilities has already started to contribute to US industrial investment. Market Intelligence forecasts show private investment in industrial facilities – across all industries – will rise by 85% in 2024 versus 2019 in inflation-adjusted terms.

The development of semiconductor production is expected to lag as plants come online and demand recovers. Our forecast calls for industrial production of semiconductors to rise by 21% in the first quarter of 2024 due to a cyclical recovery, with the investment-driven growth only starting in 2026.

While there are major investments already committed, the act doesn’t address at least three challenges that may hold back the development of the US supply chain ecosystem: vendor concentration; advanced packaging, testing and assembly; and cost increases. The act also may be causing unintended consequences, including reactions from allies and from competitors.

Strategic rivalry

Strategic rivalry between the US and EU on one side and mainland China on the other has distorted supply chains for nearly a decade and is likely to continue to do so.

Geopolitical uncertainties abound, such as the US election in November 2024 and mainland China’s position regarding Taiwan, with little apparent off-ramp from the existing cycle of restrictions and responses. Notably, US regulations include a “gray zone” of definitions, which allow the government to easily extend restrictions to new products.

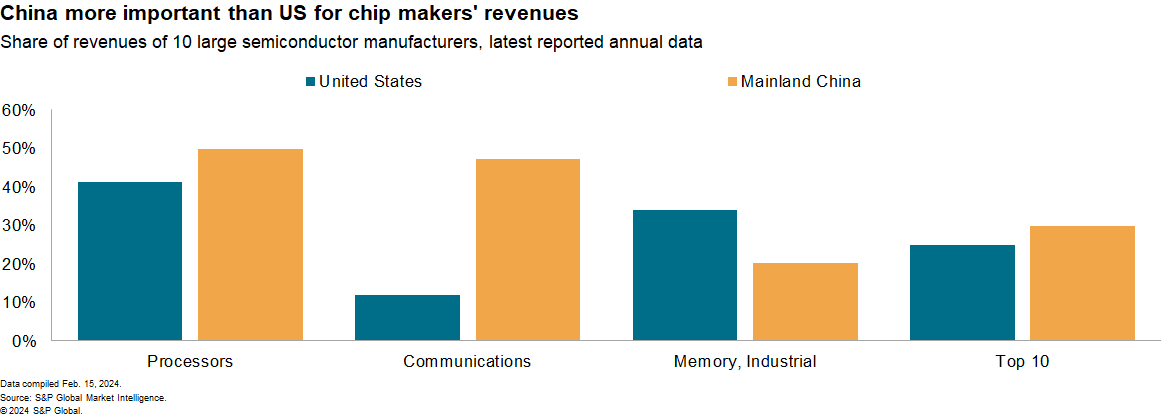

There are both limitations and potential unintended consequences to the rivalry. Mainland China remains a huge market for most of the mainstream semiconductor suppliers, equipment providers and raw material suppliers.

Our data shows mainland China accounted for 30% of the revenues of the 10 largest chip companies, which report geographic sales data, while the US accounted for 25%. Some firms have created mainland China-specific products and may need to further bifurcate their supply chains to mitigate their risks.

Illegal trade, such as black-market sales, industrial espionage and piracy, will likely increase significantly over the next few years. International research efforts and international standards-setting are also under threat — although standards have been exempted from the additional CHIPS Act guardrails. Standards such as 5G can be politicized. A breakdown of datacenter standards, open or de-facto, would bifurcate the markets.

Physical risks

Semiconductor supply chains have had to deal with a variety of physical risks over the past 10 years. These can be difficult to handle even for globally diversified firms given the often application- or technology-level specific nature of chip manufacturing equipment.

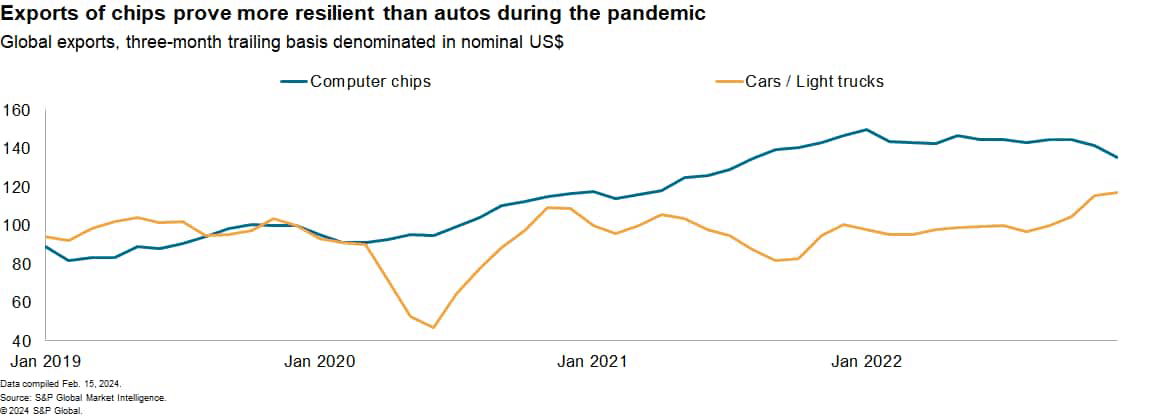

The shortages of semiconductors during the COVID-19 pandemic were arguably a demand-side problem rather than supply side. The actual closure of semiconductor fabs was minimal; rather, there was a surge in demand for consumer devices that use semiconductors.

COVID-19 accelerated the global digital transformation, with work from home putting a huge burden on IT including security leading organizations to shift their operations to the cloud, increasing demand for data center systems.

The challenges faced by the automotive sector largely reflected a decision to suspend production and orders for chips, after which the chipmakers dedicated the unused capacity to meeting consumer device requirements. It then took several order cycles for the automakers to get back into chipmakers’ order books.

Individual fabricating plants or even technology clusters are exposed to physical interruptions including war, fire or natural disasters like any other factory.

For existing plants there’s little to do to avoid physical risk, though at the corporate level it can be mitigated via geographic diversification.

The positioning of new fabricating facilities need to take climate change factors into account, particularly with regards to the availability of water — even if modern fabs have high levels of recycling.

Manufacturing and cyber security remain paramount. Products can be modified as they move through the hardware or software supply chains for corporate or political espionage.

The industry has taken seriously the allegations that backdoors could be inserted into motherboards and BIOS-level firmware with a range of trusted supply chain initiatives and networks.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here