Jorge Gaviria is the king of corn. But not the 750 billion pounds of corn grown in the U.S. for ethanol or wall plaster or shoe polish each year, the non-edible varieties that comprise 98.5% of what’s produced here.

Gaviria’s specialty is masa, the dough made from ground nixtamalized corn, the stuff of tortillas, gorditas, tamales, and pupusas. He grew up in Miami but was apprenticing at a farm-to-table restaurant in upstate New York when the idea germinated, to launch a business in nearby New York City that would do for tortillas what Tartine Bakery in San Francisco had become for sourdough—a mecca for elevated flour.

Store-bought tortillas are often mediocre, and Gaviria believed he’d find demand for a gourmet product crafted from heirloom corn.

More: People Are Paying Hundreds, or Thousands, to Learn How to Breathe

After some research, he found Masa harina, the pre-ground flower that makes tortilla making easy, “impossible to screw up,” and a huge improvement over the bland options found in supermarkets.

But Gaviria kept investigating, landing a job at a taco shop in Manhattan’s East Village and scouring farmer’s markets for the best flour he could find. He traveled to Oaxaca, Mexico, which many consider the global capital of masa, home to some of the best heirloom corn in the country.

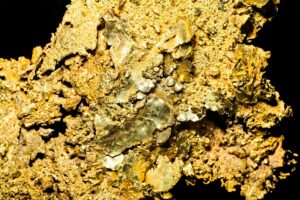

He met with growers across the region’s central valley and learned why this corn and the masa made from it were so much better than what he’d found anywhere else: companion planting and nutritious soil.

He learned that local molineros deployed special milling stones, to achieve the perfect texture in their dough, and the tortillas. The secret to better tortillas was woven throughout the entire process. Inspired, Gaviria set out to build a fair-trade supply chain throughout rural Mexico, and he found a New York chef who agreed to buy all the single-origin Mexican heirloom corn he could source.

That endeavor grew and grew, until Gaviria launched Masienda in 2014 and was providing high-quality corn and masa to dozens of restaurants. By 2021, Gaviria’s company had sourced more than 6 million pounds of heirloom corn, carving out a stable spot in the US$48 billion global tortilla market. The company is now headquartered in Los Angeles, with a team on the ground in Mexico and 14 total employees. In 2022, Gaviria published the first comprehensive book on the product, simply called Masa, which was nominated for a James Beard Award and a national bestseller.

More: The Key to a Long Life: Caring for Your Mitochondria

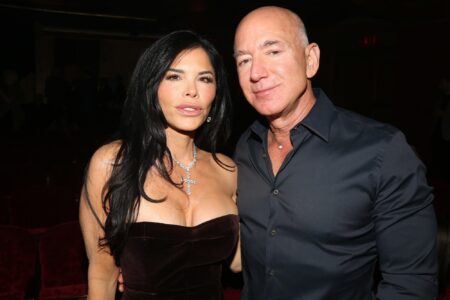

Gaviria, 36, speaks with Penta about his company, and the rise of the home tortilleria.

So, why masa?

I was working in fine dining, at a restaurant called Blue Hill Stone Barns [in Tarrytown, New York], which felt like ground zero for the farm-to-table conversation in the U.S. I saw how much of an impact the ideas coming out of the kitchen had on consumer culture. Over time, you could trace any number of food trends that were taking shape on grocery shelves to [chef

Dan Barber’s

] kitchen, and certainly for that matter a lot of high-end kitchens across the country were challenging the way we think and approach food. Dan was working on supply chains, regenerative agriculture, soil health, food for flavor’s sake and not for yield’s sake, getting back to the way we eat and how to get as much pleasure from that process as possible. I wanted to see the foods I grew up with reflected in that conversation. I wanted to see Latin cuisine parity. For me, the impulse was really just that, and I thought “What’s the most logical place to start here?” Masa is the connective tissue across Latin America. It’s a huge tradition, and arguably where it all started was in Mexico. A little mystery around that, a significant staple, it just felt like a really compelling place to start.

Has corn been unfairly maligned?

It’s been the poster child for the industrialization of agriculture. Commodity dumping, global trade wars, it’s come to represent a lot more than really the sacrosanct origin story that is still relayed in Mexico and still really believed and practiced to this day. It transcends a commodity or ingredient. We and corn are inextricably linked. There’s a religious, a sort of spiritual element to it that’s hard to relate to when we think about genetically modified corn, or corn for ethanol. We’ve come very far away from the origin of the food. The idea of using it for wall plaster is anathema to the communities that still grow it. We’ve been very creative as humans to find uses and byproducts for things. We’ve been very clever to do that. But it’s come at the expense of the tradition and wisdom we spent so much time cultivating.

More: Six Artful Dragon-Themed Watches to Fire up the Lunar New Year

Are we consuming too much, or the wrong kind of corn’s byproducts?

The average Mexican eats per capita, I want to say, it’s close to 200 pounds of corn per year. If you’re eating that much, the hope is that it’s good. When you think about corn as a real foundation of a diet, when it’s taken in conjunction with beans and squash, these really ancestral complementary foods and agricultural processes, it all makes sense. When you start to cherry pick and remove that from its context or the ecology that made it possible, you start to complicate things. That’s really what’s happened over the last 100 years. As has happened with many industrialized foods, it’s not limited to corn. We lose a lot of the trial and error, the wisdom we’ve gleaned over millennia.

Is it a challenge to convince people that they should return to corn’s roots?

It’s always a challenge. But it’s a fun one. To some extent, that challenge has been mitigated by the pandemic, which really forced a lot of us to re-examine our relationship with food, whether it was boredom or scarcity or necessity. It was a boon to active consumption, versus the passive consumption we’d become used to in our lifetime.

That was a helpful tailwind going into direct-to-consumer and home cooks, versus being focused on restaurants. Masienda really started as a food service brand, a b2b brand. Even those folks who grew up eating tortillas and had family that made them can be spoiled by the excesses we’ve created over these last few generations. It’s very humbling to get back to the roots, especially for millennials and folks becoming parents. They’re finding ways to relate to themselves through this food, these staples. It’s very powerful. If there’s a lost connection to the family member who would have passed that wisdom on and are able to stay connected to, it certainly makes for a deeper appreciation at the least. In most cases, people find it’s a lot easier than it looks, certainly to have a really good-quality taco or sope or tamal. It’s a game changer to just try doing it yourself.

What kind of people are you working the hardest to reach?

It’s everybody, honestly, but we break it up into two camps. There’s a strong focus on roots cooks, who might require a little bit less education, information or context around what masa is because it’s built into the ancestral lineage that they come from and we come from. The other is project cooks, or more traditional cooking. When you start to play with masa and get your hands in it, you have a much deeper appreciation for not just the process but hopefully the culture behind it. It’s a humbling experience.

More: ‘Seinfeld’ Producer Andrew Scheinman Lists $17.75 Million L.A. Mansion

What’s next for Masienda?

We’ve been building since the pandemic. We have a really strong online base. We’re getting in front of new customers, building a new tribe. There’s an amazing creative team, where for the first time we’ve applied a brand-storytelling approach to the supply chain we’ve been building from the beginning. There’s no substitute for retail grocery if you’re in food, so we’re definitely finding ways to creatively make an impact in that space. We’re obviously going with some of the folks that might be table stakes for getting a start, like a Whole Foods, and we also want to be working in places our core consumer wants us to be in, like Mexican grocers, Latin grocers. We’re really focused on trying to make that transition responsibly.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Read the full article here